|

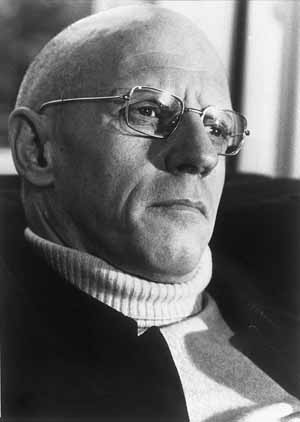

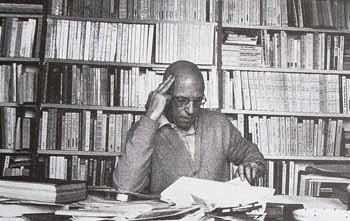

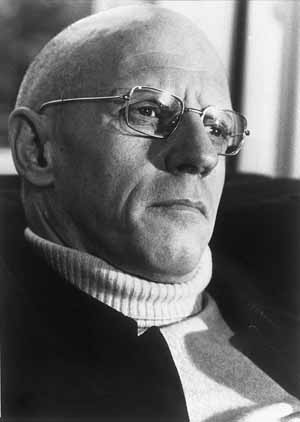

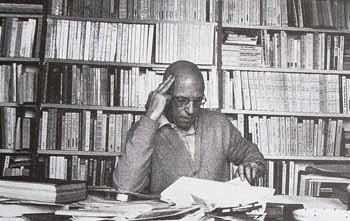

Profiles > Philosophy > Michel Foucault

|

| Michel Foucault |

|

Michel Foucault (1926-1984) was a French philosopher, historian of ideas, social theorist, philologist and literary critic. His theories addressed the relationship between power and knowledge, and how they are used as a form of social control through societal institutions. Though often cited as a post-structuralist and post-modernist, Foucault ultimately rejected these labels, preferring to classify his thought as a critical history of modernity. His thought has been highly influential for both academic and activist groups. Born in Poitiers, France to an upper-middle-class family, Foucault was educated at the Lycée Henri IV and then the École Normale Supérieure, where he developed an interest in philosophy and came under the influence of his tutors Jean Hyppolite and Louis Althusser. After several years as a cultural diplomat abroad, he returned to France and published his first major book, The History of Madness. After obtaining work between 1960 and 1966 at the University of Clermont-Ferrand, he produced two more significant publications, The Birth of the Clinic and The Order of Things, which displayed his increasing involvement with structuralism, a theoretical movement in social anthropology from which he later distanced himself. These first three histories were examples of a historiographical technique Foucault was developing which he called archaeology.Early Life Paul-Michel Foucault was born on 15 October 1926 in the small town of Poitiers, west-central France, as the second of three children to a prosperous and socially conservative upper-middle-class family. He had been named after his father, Dr. Paul Foucault, as was the family tradition, but his mother insisted on the addition of the double-barreled

|

|

|

"Michel"; referred to as "Paul" at school, throughout his life he always expressed a preference for "Michel". His father (1893–1959) was a successful local surgeon, having been born in Fontainebleau before moving to Poitiers, where he set up his own practice and married local woman Anne Malapert. She was the daughter of prosperous surgeon Dr. Prosper Malapert, who owned a private practice and taught anatomy at the University of Poitiers' School of Medicine. Paul Foucault eventually took over his father-in-law's medical practice, while his wife took charge of their large mid-19th-century house, Le Piroir, in the village of Vendeuvre-du-Poitou. Together the couple had three children -- a girl named Francine, and two boys, Paul-Michel and Denys, all of whom shared the same fair hair and bright blue eyes. The children were raised to be nominal Roman Catholics, attending mass at the Church of Saint-Porchair, and while Michel briefly became an altar boy, none of the family was devout.

|

|

| Three other factors were of much more positive significance for the young Foucault. First, there was the French tradition of history and philosophy of science, particularly as represented by Georges Canguilhem, a powerful figure in the French University establishment, whose work in the history and philosophy of biology provided a model for much of what Foucault was later to do in the history of the human sciences. Canguilhem sponsored Foucault's doctoral thesis on the history of madness and, throughout Foucault's career, remained one of his most important and effective supporters. Canguilhem's approach to the history of science (an approach developed from the work of Gaston Bachelard), provided Foucault with a strong sense of the discontinuities in scientific history, along with a "rationalist" understanding of the historical role of concepts that made them independent of the phenomenologists' transcendental consciousness. Foucault found this understanding reinforced in the structuralist linguistics and psychology developed, respectively, by Ferdinand de Saussure and Jacques Lacan, as well as in Georges Dumézil's proto-structuralist work on comparative religion. |

| Born |

15 October 1926 / Poitiers |

| Died |

25 June 1984 / Paris |

| Nationality |

French |

| Era |

20th Century Philosophy |

| School |

Western Philosophy |

| Main Interests |

History of Ideas, Epistemology, ethics, political, philosophical |

| Notable Ideas |

Disciplinary institution, Govern mentality, Power, Knowledge |

|

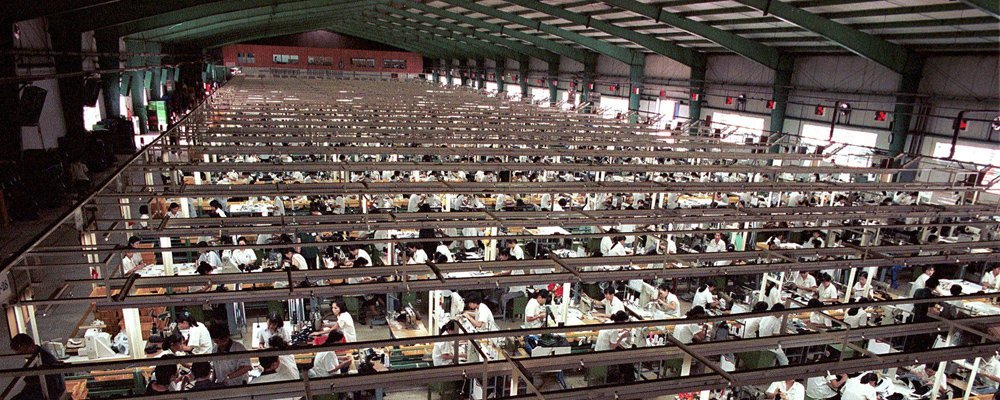

| These anti-subjective standpoints provide the context for Foucault's marginalization of the subject in his structuralist histories -- The Birth of the Clinic (on the origins of modern medicine) and The Order of Things (on the origins of the modern human sciences). |

|

Foucault's Critiques of Historical Reason

|

|

Foucault's first major work, History of Madness in the Classical Age (1961) originated in his academic study of psychology (a licence de psychologie in 1949 and a diplome de psycho-pathologie in 1952), his work in a Parisian mental hospital, and his own personal psychological problems. It was mainly written during his post-graduate Wanderjahren (1955-1959 journeyman years) through a succession of diplomatic/educational posts in Sweden, Germany, and Poland. A study of the emergence of the modern concept of "mental illness" in Europe, History of Madness is formed from both Foucault's extensive archival work and his intense anger at what he saw as the moral hypocrisy of modern psychiatry. Standard histories saw the nineteenth-century medical treatment of madness (developed from the reforms of Pinel in France and the Tuke brothers in England) as an enlightened liberation of the mad from the ignorance and brutality of preceding ages. According to Foucault, the new idea that the mad were merely sick ("mentally" ill) and in need of medical treatment was not at all a clear improvement on earlier conceptions (e.g., the Renaissance idea that the mad were in contact with the mysterious forces of cosmic tragedy or the 17th-18th-century view of madness as a renouncing of reason). Moreover, he argued that the alleged scientific neutrality of modern medical treatments of insanity are in fact covers for controlling challenges to a conventional bourgeois morality. In short, Foucault argued that what was presented as an objective, incontrovertible scientific discovery (that madness is mental illness) was in fact the product of eminently questionable social and ethical commitments. Foucault's next history, The Birth of the Clinic (1963) can similarly be read as a critique of modern clinical medicine. But the socio-ethical critique is muted (except for a few vehement passages), presumably because there is a substantial core of objective truth in medicine (as opposed to psychiatry) and so less basis for critique. As a result The Birth of the Clinic is much closer to a standard history of science, in the tradition of Canguilhem's history of concepts.

|

The Order of Things

|

|

The book that made Foucault famous, Les mots et les choses -- translated into English under the title The Order of Things -- is in many ways an odd interpolation into the development of his thought. Its sub-title, "An Archaeology of the Human Sciences", suggests an expansion of the earlier critical histories of psychiatry and clinical medicine into other modern disciplines such as economics, biology, and philology. Indeed there is an extensive account of the various "empirical disciplines" of the Renaissance and the Classical Age that precede these modern human sciences. There is little or nothing of the implicit social critique found in the History of Madness or even The Birth of the Clinic. Instead, Foucault offers a global analysis of what knowledge meant -- and how this meaning changed -- in Western thought from the Renaissance to the present. At the heart of his account is the notion of representation. It is in his treatment of representation in philosophical thought, where we find Foucault's most direct engagement with traditional philosophical questions. Foucault maintained a keen interest in literature, publishing reviews in literary journals Tel Quel and Nouvelle Revue Française, and sitting on the editorial board of Critique. In May 1963, he published a book devoted to poet, novelist, and playwright Raymond Roussel. It was written in under two months, published by Gallimard, and would be described by biographer David Macey as "a very personal book" that resulted from a "love affair" with Roussel's work. It would be published in English in 1983 as Death and the Labyrinth: The World of Raymond Roussel. Receiving few reviews, it was largely ignored. That same year he published a sequel to Folie et déraison, entitled Naissance de la Clinique, subsequently translated as Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception. Shorter than its predecessor, it focused on the changes that the medical establishment underwent in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Like his preceding work, Naissance de la Clinique was for the most part critically ignored, but later gained a cult following. Foucault was also selected to be among the "Eighteen Man Commission" that assembled between November 1963 and March 1964 to discuss university reforms that were to be implemented by Christian Fouchet, the Gaullist1 Minister of National Education. Implemented in 1967, they brought staff strikes and student protests. The book that made Foucault famous, Les mots et les choses -- translated into English under the title The Order of Things -- is in many ways an odd interpolation into the development of his thought. Its sub-title, "An Archaeology of the Human Sciences", suggests an expansion of the earlier critical histories of psychiatry and clinical medicine into other modern disciplines such as economics, biology, and philology. Indeed there is an extensive account of the various "empirical disciplines" of the Renaissance and the Classical Age that precede these modern human sciences. There is little or nothing of the implicit social critique found in the History of Madness or even The Birth of the Clinic. Instead, Foucault offers a global analysis of what knowledge meant -- and how this meaning changed -- in Western thought from the Renaissance to the present. At the heart of his account is the notion of representation. It is in his treatment of representation in philosophical thought, where we find Foucault's most direct engagement with traditional philosophical questions. Foucault maintained a keen interest in literature, publishing reviews in literary journals Tel Quel and Nouvelle Revue Française, and sitting on the editorial board of Critique. In May 1963, he published a book devoted to poet, novelist, and playwright Raymond Roussel. It was written in under two months, published by Gallimard, and would be described by biographer David Macey as "a very personal book" that resulted from a "love affair" with Roussel's work. It would be published in English in 1983 as Death and the Labyrinth: The World of Raymond Roussel. Receiving few reviews, it was largely ignored. That same year he published a sequel to Folie et déraison, entitled Naissance de la Clinique, subsequently translated as Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception. Shorter than its predecessor, it focused on the changes that the medical establishment underwent in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Like his preceding work, Naissance de la Clinique was for the most part critically ignored, but later gained a cult following. Foucault was also selected to be among the "Eighteen Man Commission" that assembled between November 1963 and March 1964 to discuss university reforms that were to be implemented by Christian Fouchet, the Gaullist1 Minister of National Education. Implemented in 1967, they brought staff strikes and student protests.

|

|

|

In April 1966, Gallimard published Foucault's Les Mots et les Choses, later translated as The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. Exploring how man came to be an object of knowledge, it argued that all periods of history have possessed certain underlying conditions of truth that constituted what was acceptable as scientific discourse. Foucault argues that these conditions of discourse have changed over time, from one period's episteme to another. Although designed for a specialist audience, the work gained media attention, becoming a surprise bestseller in France. Appearing at the height of interest in structuralism, Foucault was quickly grouped with scholars Jacques Lacan, Claude Lévi-Strauss, and Roland Barthes, as the latest wave of thinkers set to topple the existentialism popularized by Jean-Paul Sartre. Although initially accepting this description, Foucault soon vehemently rejected it. Foucault and Sartre regularly criticized one another in the press; both Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir attacked Foucault's ideas as "bourgeoisie", while Foucault retaliated against their Marxist beliefs by proclaiming that "Marxism exists in nineteenth-century thought as a fish exists in water; that is, it ceases to breathe anywhere else.

|

|

|

| The History of Sexuality and the Iranian Revolution: 1976-1979 |

In 1976 Gallimard published Foucault's Histoire de la sexualité: la volonté de savoir (The History of Sexuality: The Will to Knowledge), a short book exploring what Foucault called the repressive hypothesis. It revolved largely around the concept of power, with Foucault rejecting the Marxist theories of power as well as breaking with psychoanalysis. Foucault intended for it to be the first in a seven-volume exploration of the subject. Histoire de la sexualité was a best seller and gained positive press reception, but lukewarm intellectual interest, something that upset Foucault, who felt that many misunderstood his hypothesis. He soon became dissatisfied with Gallimard after being offended by senior staff member Pierra Nova. Along with Paul Veyne and François Wahl, Foucault launched a new series of academic books, known as Dex Travaux (Some Works), through the company Seuil, which he hoped would improve the state of academic research in France. He also produced introductions for the memoirs of Herculine Barbin and My Secret Life. In 1976 Gallimard published Foucault's Histoire de la sexualité: la volonté de savoir (The History of Sexuality: The Will to Knowledge), a short book exploring what Foucault called the repressive hypothesis. It revolved largely around the concept of power, with Foucault rejecting the Marxist theories of power as well as breaking with psychoanalysis. Foucault intended for it to be the first in a seven-volume exploration of the subject. Histoire de la sexualité was a best seller and gained positive press reception, but lukewarm intellectual interest, something that upset Foucault, who felt that many misunderstood his hypothesis. He soon became dissatisfied with Gallimard after being offended by senior staff member Pierra Nova. Along with Paul Veyne and François Wahl, Foucault launched a new series of academic books, known as Dex Travaux (Some Works), through the company Seuil, which he hoped would improve the state of academic research in France. He also produced introductions for the memoirs of Herculine Barbin and My Secret Life.

|

|

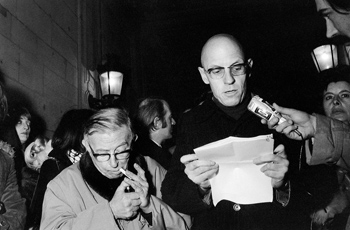

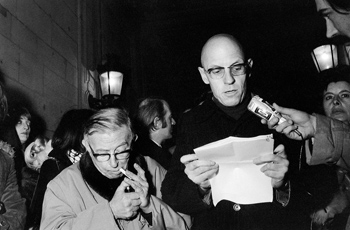

Foucault remained a political activist, focusing his attention on protesting government abuses of human rights across the world. He was a key player in the 1975 protests against the Spanish government to execute 11 militants sentenced to death without a fair trial. It was his idea to travel to Madrid with six others to give their press conference there; they were subsequently arrested and deported back to Paris. In 1977, he suffered a fractured rib during clashes with riot police as he protested the extradition of Klaus Croissant to West Germany. In July of that year he organized an assembly of Eastern Bloc dissidents to mark the visit of Soviet Premier Leonid Brezhnev to Paris, and in 1979 he campaigned for Vietnamese political dissidents to be granted asylum in France.

|

|

On 26 June, Libération announced his death, mentioning the rumor that it had been brought on by AIDS. The following day, Le Monde issued a medical bulletin cleared by his family which made no reference to HIV/AIDS.[ On 29 June, Foucault's la levée du corps ceremony was held, in which the coffin was carried from the hospital morgue. Hundreds attended, including activist and academic friends, while Gilles Deleuze gave a speech using text from The History of Sexuality. His body was then buried at Vendeuvre in a small ceremony. Soon after his death, Foucault's partner Daniel Defert founded the first national HIV/AIDS organization in France, AIDES; a pun on the French language word for "help" (aide) and the English language acronym for the disease. On the second anniversary of Foucault's death, Defert publicly revealed that Foucault's death was AIDS-related in California-based gay magazine, The Advocate.

|

|

|

Credits

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michel_Foucault

www.egs.edu/library/michel-foucault/biography/

http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/foucault/

|

1 French political ideology based on the thought and action of Resistance leader then President Charles de Gaulle.

|

|

The book that made Foucault famous, Les mots et les choses -- translated into English under the title

The book that made Foucault famous, Les mots et les choses -- translated into English under the title  In 1976 Gallimard published Foucault's Histoire de la sexualité: la volonté de savoir (The History of Sexuality: The Will to Knowledge), a short book exploring what Foucault called the repressive hypothesis. It revolved largely around the concept of power, with Foucault rejecting the Marxist theories of power as well as breaking with psychoanalysis. Foucault intended for it to be the first in a seven-volume exploration of the subject. Histoire de la sexualité was a best seller and gained positive press reception, but lukewarm intellectual interest, something that upset Foucault, who felt that many misunderstood his hypothesis. He soon became dissatisfied with Gallimard after being offended by senior staff member Pierra Nova. Along with Paul Veyne and François Wahl, Foucault launched a new series of academic books, known as Dex Travaux (Some Works), through the company Seuil, which he hoped would improve the state of academic research in France. He also produced introductions for the memoirs of Herculine Barbin and My Secret Life.

In 1976 Gallimard published Foucault's Histoire de la sexualité: la volonté de savoir (The History of Sexuality: The Will to Knowledge), a short book exploring what Foucault called the repressive hypothesis. It revolved largely around the concept of power, with Foucault rejecting the Marxist theories of power as well as breaking with psychoanalysis. Foucault intended for it to be the first in a seven-volume exploration of the subject. Histoire de la sexualité was a best seller and gained positive press reception, but lukewarm intellectual interest, something that upset Foucault, who felt that many misunderstood his hypothesis. He soon became dissatisfied with Gallimard after being offended by senior staff member Pierra Nova. Along with Paul Veyne and François Wahl, Foucault launched a new series of academic books, known as Dex Travaux (Some Works), through the company Seuil, which he hoped would improve the state of academic research in France. He also produced introductions for the memoirs of Herculine Barbin and My Secret Life.